In large companies, design sounds risky and introduces a myriad of questions. How does design fit into business? How does collaborative design function effectively at the enterprise level? How do we design at scale while avoiding the risks and uncertainties? For many organizations, design thinking has provided a good solution to this problem space.

This has led many in life sciences to question how design thinking and UX relate to one another. Why do we have two similar-sounding processes in our field?

Design Thinking and UX are by and large the same things. Their goals are essentially the same. Put users at the forefront of your mind when designing creative solutions whether they are digital or physical. They use the same methods such as personas, empathy maps, and user journeys. They follow a similar design trajectory of understanding the user, designing solutions, and evaluating them against the user. They use a similar team ethos of using a multi-disciplinary team to come up with the best solution.

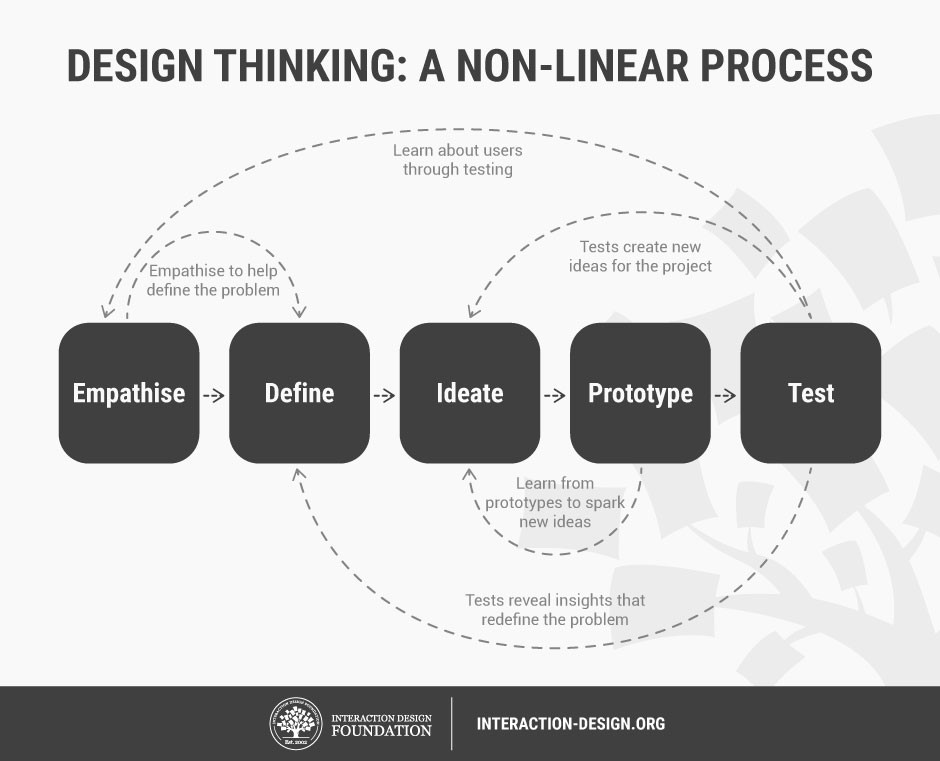

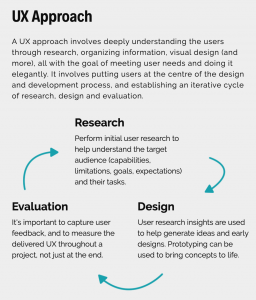

Traditionally the UX approach has been used to describe design in a digital landscape and design thinking can be applied to any problem space. To be fair the UX approach would likely work in any problem space. Although design thinking is often described in a linear process diagram most people would practise it iteratively as can be seen from Figure A from the Interaction Design Foundation. Compared to the UX approach in Figure B one can see the immediate commonalities.

Figure A: Design Thinking process is practiced in a non-linear fashion as shown by the Interaction Design Foundation. (Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Figure B: The UX approach as described in the UXLS toolkit.

Why has design thinking been so popular?

The concepts behind Design Thinking are not new, in fact many of the foundations came out of systematic design methods from the 1950s and ‘60s, however Design Thinking as a process to invoke creative action began emerging in the 1980s, initially at Stanford University (who’s 5-step process is commonly referred to as the Stanford Model) and through large design agencies such as IDEO.

Since then, Design Thinking has become increasingly popular due to its apparent ability to find solutions to complex problems in a time-boxed fashion. In the age where we value time-to-market, agility and “fail quick” attitudes, this has appealed to executives who see Design Thinking as the antithesis of analysis paralysis and over-engineered solutions, whilst those involved in design activities relish the drive and focus Design Thinking encourages, bringing out the creativity and collaborative spirit of those who take part.

Another reason for its popularity is, perhaps counterintuitively, down to the conceptuality and inherent ambiguity of the process – it can be as easily applied to urban planning as it can to a new website. This universal relevance means that, upon searching for it on the web, anybody can immediately see how it might benefit their area.

Fundamentally, Design Thinking appeals to our deep-down realisation that many of the challenges we face in our roles are not easy, and any tool that can sell itself as finding solutions quickly and creatively is bound to appeal to those looking for better ways of working.

The Design Thinking model is flexible and generally applicable to a wider range of problems than UX design. The methodology is easy to explain, teach, and educate for larger teams as it has the “Google factor” allowing people to learn about the process from a wide variety of sources and viewpoints. The methodology also aligns well with common business process based thinking and its clear structure makes it familiar to “non-design” oriented people. Design thinking fits well in a project-oriented structure due to its origin and adoption by service companies. If your team is exploring an idea or attempting to work through a complex, multi-faceted problem — design thinking an excellent choice.

So what are the differences between Design Thinking and UX?

So perhaps you are thinking what is the difference between design thinking and UX. Well the answer is not much but if we were to attempt to disentangle these terms – this would be our thinking.

Design Thinking can be used to solve complicated problems and combine user needs with business expectations. The final result should include a good value proposition, which is a promise of a specific benefit that will be delivered to the user. The process focuses on creating a concept of product or service which is tested on its last phase. Much time is devoted to exploring the concept itself and checking whether it responds to actual needs and if there’s a place for it on the market. This can make the initial phase of the process very long. However the dedicated space to empathise, define and ideate allows the team to really get to grips with the problem.

UX is very similar to Design Thinking but rather than the broader remit of designing for any design problem, UX is associated with the design of digital software and products. In its toolkit it may have some methods more closely associated to the digital landscape such as AB testing or SUS scores.

Whichever methodology you choose to utilize, it is important to remember that they are just tools to solve problems. Work with your teams to try different approaches, adjust, and use what works. What is most important is that your work does not lose the creativity, ideas, and variability at the heart of design. These processes are like a recipe — the first time you may follow it to the letter — but the right amount of spices and creative magic might come later after cooking the dish many times.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our reviewers Rob Graham (AstraZeneca) and Charlie Hathaway (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute) for their thoughtful contribution.

Header image attribution: Peas by “Liz West” CC BY 2.0